STARDUST

Photographs are illusions. In a popular text from 1980, the American essayist Susan Sontag compares the photographic image with the shadow play in the famous cave of the philosopher Plato. In spirit this would make the Greek thinker of the fifth century BC the first photographer in world history. Plato's parable of the prisoners in a dark cave, who only ever perceive the shadows of the apparitions through a split of light, has mutated from the classic of philosophical idealism to the basic motive of photographic theory.

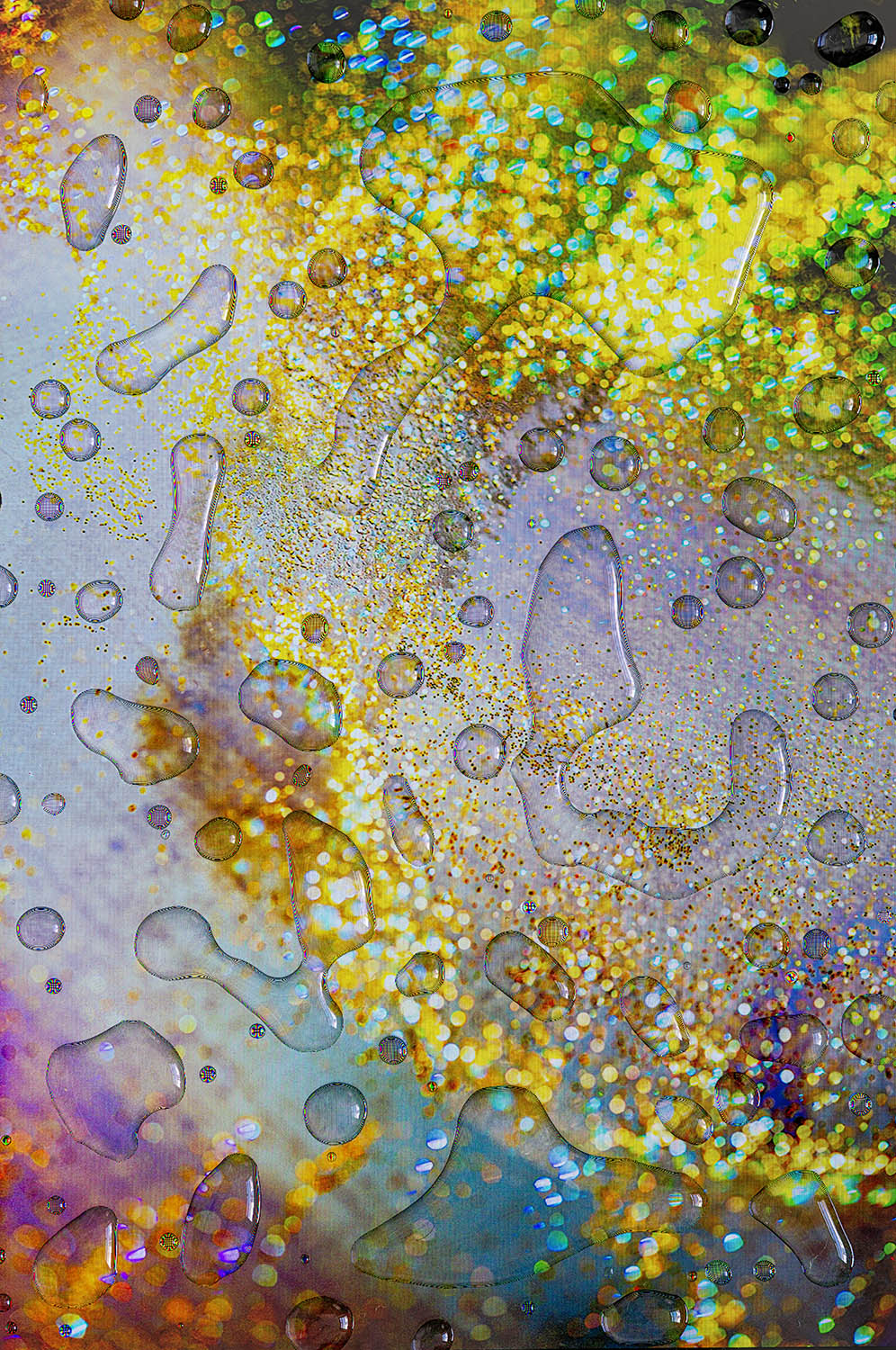

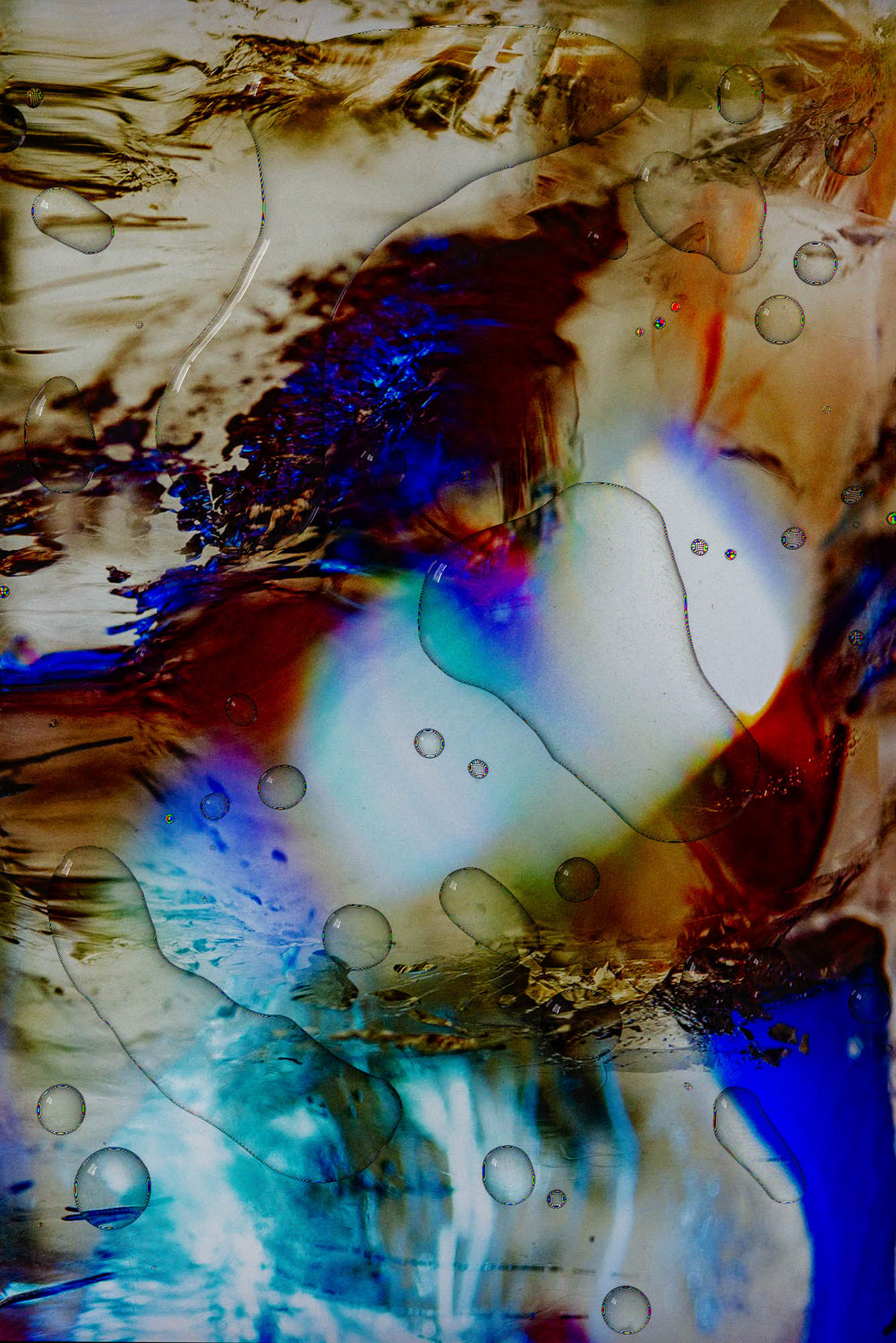

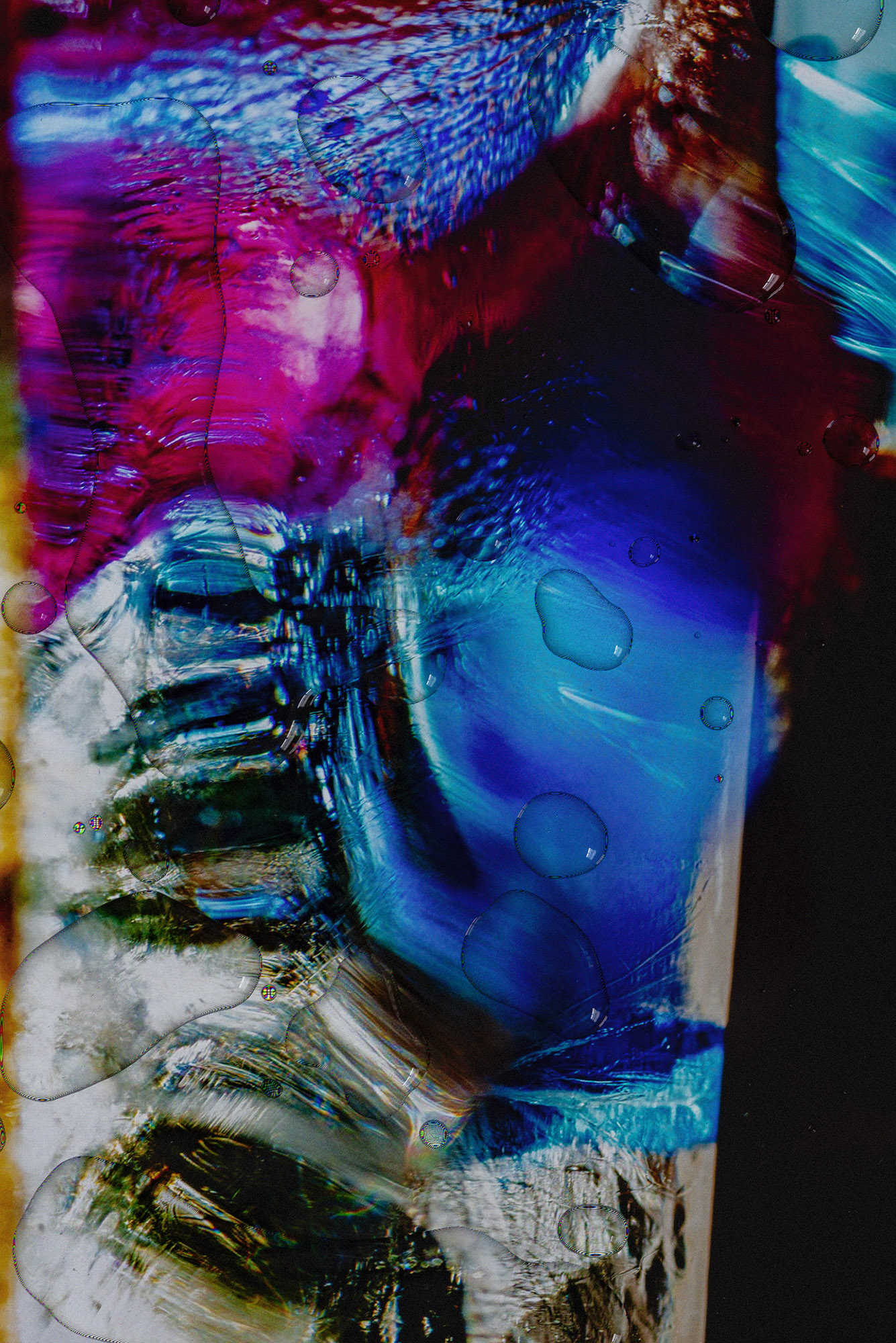

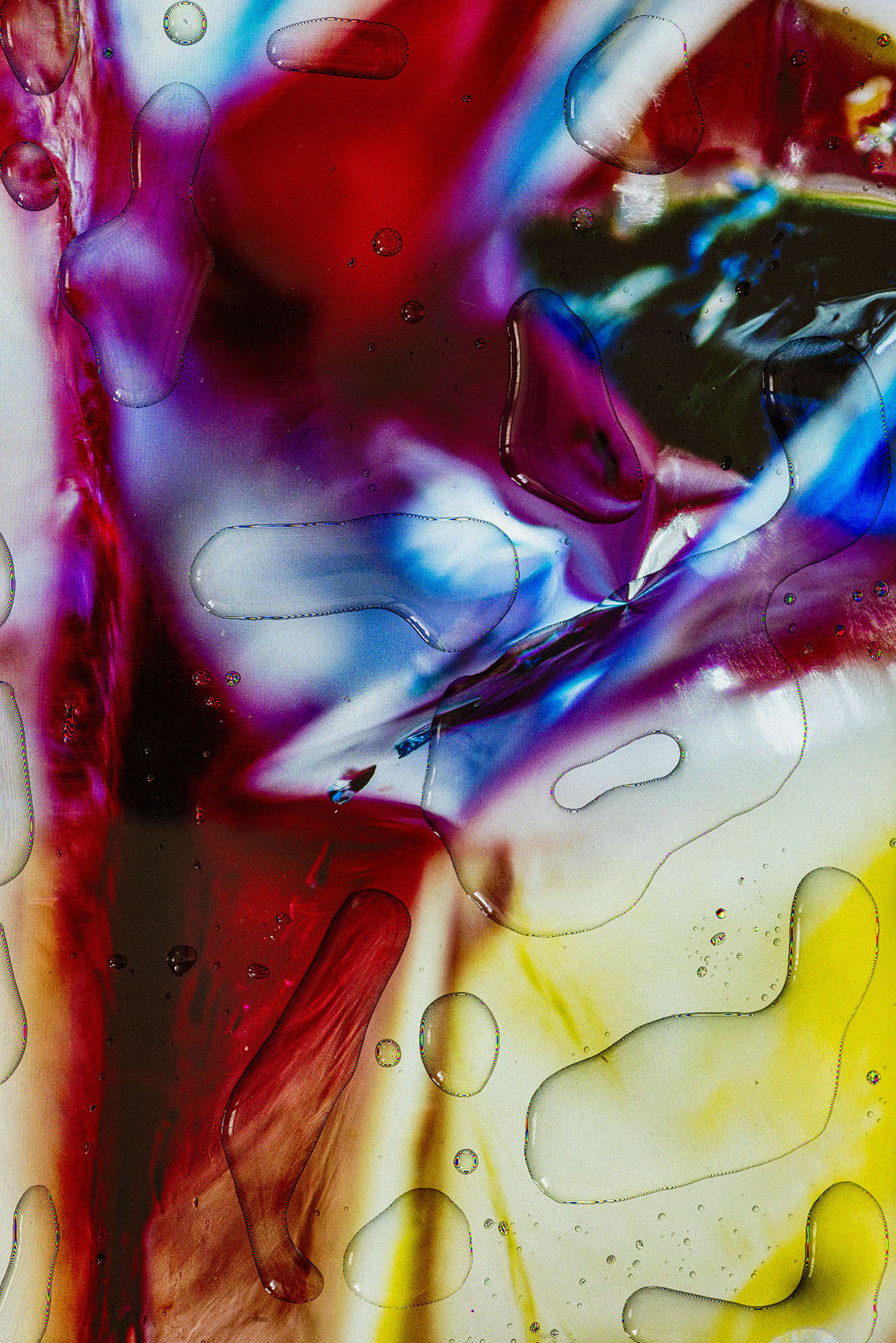

Presumably, Martin Ogolter also had the image of those trapped in rock and ignorance in mind when he made his first foray into his series “Stardust” in 2016 - a series based in content on the numerous connections between light, time and reality, but at first glance, at the picture level, only delivers abstractions and riddles. By draping flowers frozen in a block of ice on a mirror, photographing the plants thawing in the sunlight, and finally photographing the final image from an iPad screen, the artist subtly points out the many transformations and information shifts in the long process between image and picture. It seems as if the photograph was somehow related to the eponymous stardust - with informational units that emanate from mostly tiny matter particles in interstellar space, and whose light often takes tens of thousands of years to move from sheer infinity to the tiny world of our perception.

Stardust also brought to light in Ogolter's work “pastPresentfuture”, composed of many single images: In a way, we are still sitting in Plato's cave. We never see microcosms or macrocosms with our photographic equipment and their images; we only see their traces - light, fragments, poetic dust. Especially in a time when we increasingly perceive the world via technical data and iconographic pixelations, more and more medial processes are required - more and more detours and more and more time - until the pictures of a supposed reality burn themselves as images on our retina. It is precisely this growing difference that is repeatedly raised by Martin Ogolter in his work; Interestingly enough, this difference does not make our world clearer or more familiar, but in the end it makes us seem increasingly abstract and alien.

—Ralf Hanselle

STARDUST

Fotografias são ilusões. Em um texto popular de 1980, a ensaísta americana Susan Sontag compara a imagem fotográfica com o jogo de sombras na famosa caverna do filósofo Platão. Em espírito, isso faria do pensador grego do século V a.C. o primeiro fotógrafo da história mundial. A parábola de Platão sobre os prisioneiros em uma caverna escura, que só percebem as sombras das aparições através de uma divisão de luz, sofreu mutação do clássico do idealismo filosófico para o motivo básico da teoria fotográfica.

Presumivelmente, Martin Ogolter também tinha a imagem daqueles presos na rocha e na ignorância em mente quando fez sua primeira incursão em sua série “Stardust” em 2016 - uma série baseada em conteúdo nas inúmeras conexões entre luz, tempo e realidade, mas à primeira vista, no nível da imagem, apenas fornece abstrações e enigmas. Ao pendurar flores congeladas em um bloco de gelo em um espelho, fotografar as plantas descongelando na luz do sol e, finalmente, fotografar a imagem final de uma tela de iPad, o artista sutilmente aponta as muitas transformações e mudanças de informação no longo processo entre imagem e foto. Parece que a fotografia estava de alguma forma relacionada à poeira estelar homônima - com unidades informacionais que emanam principalmente de partículas de matéria minúsculas no espaço interestelar, e cuja luz frequentemente leva dezenas de milhares de anos para se mover do infinito absoluto para o pequeno mundo de nossa percepção.

A poeira estelar também é trazida à luz na obra de Ogolter "pastPresentfuture", composta de muitas imagens únicas: De certa forma, ainda estamos sentados na caverna de Platão. Nunca vemos microcosmos ou macrocosmos com nosso equipamento fotográfico e suas imagens; vemos apenas seus traços - luz, fragmentos, poeira poética. Especialmente em uma época em que percebemos cada vez mais o mundo por meio de dados técnicos e pixelizações iconográficas, mais e mais processos mediais são necessários - mais e mais desvios e mais e mais tempo - até que as imagens de uma suposta realidade se queimem como imagens em nossa retina. É precisamente essa diferença crescente que é repetidamente levantada por Martin Ogolter em seu trabalho; Curiosamente, essa diferença não torna nosso mundo mais claro ou mais familiar, mas no final nos faz parecer cada vez mais abstratos e estranhos.

—Ralf Hanselle

untitled (Stardust B034), pigment print, 120x180cm,

untitled (Stardust B036), pigment print, 150x100cm

untitled (Stardust B02), pigment print, 100x150cm